The Inamorta by Joshua Rex

The Inamorta by Joshua Rex

16 in stock

Couldn't load pickup availability

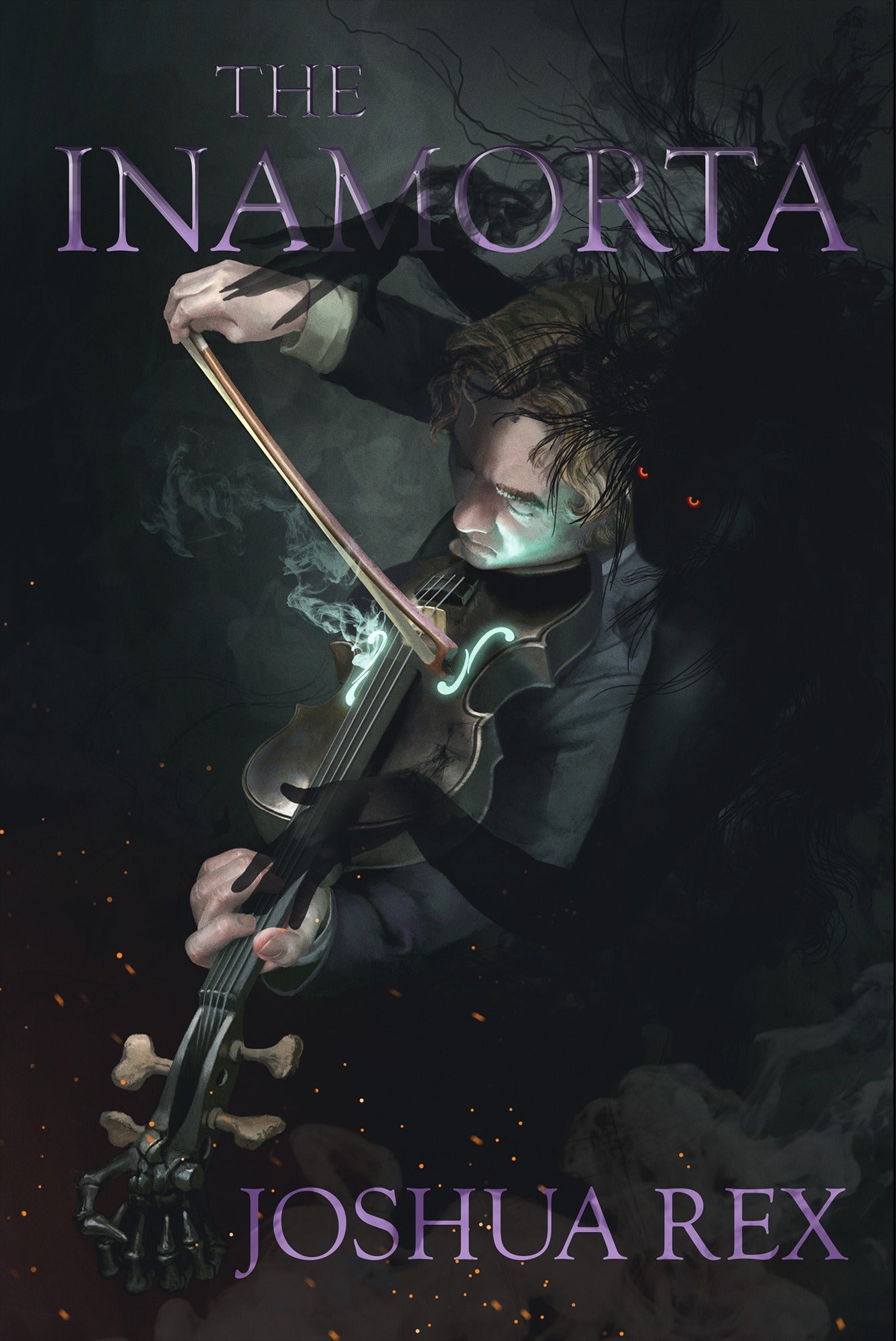

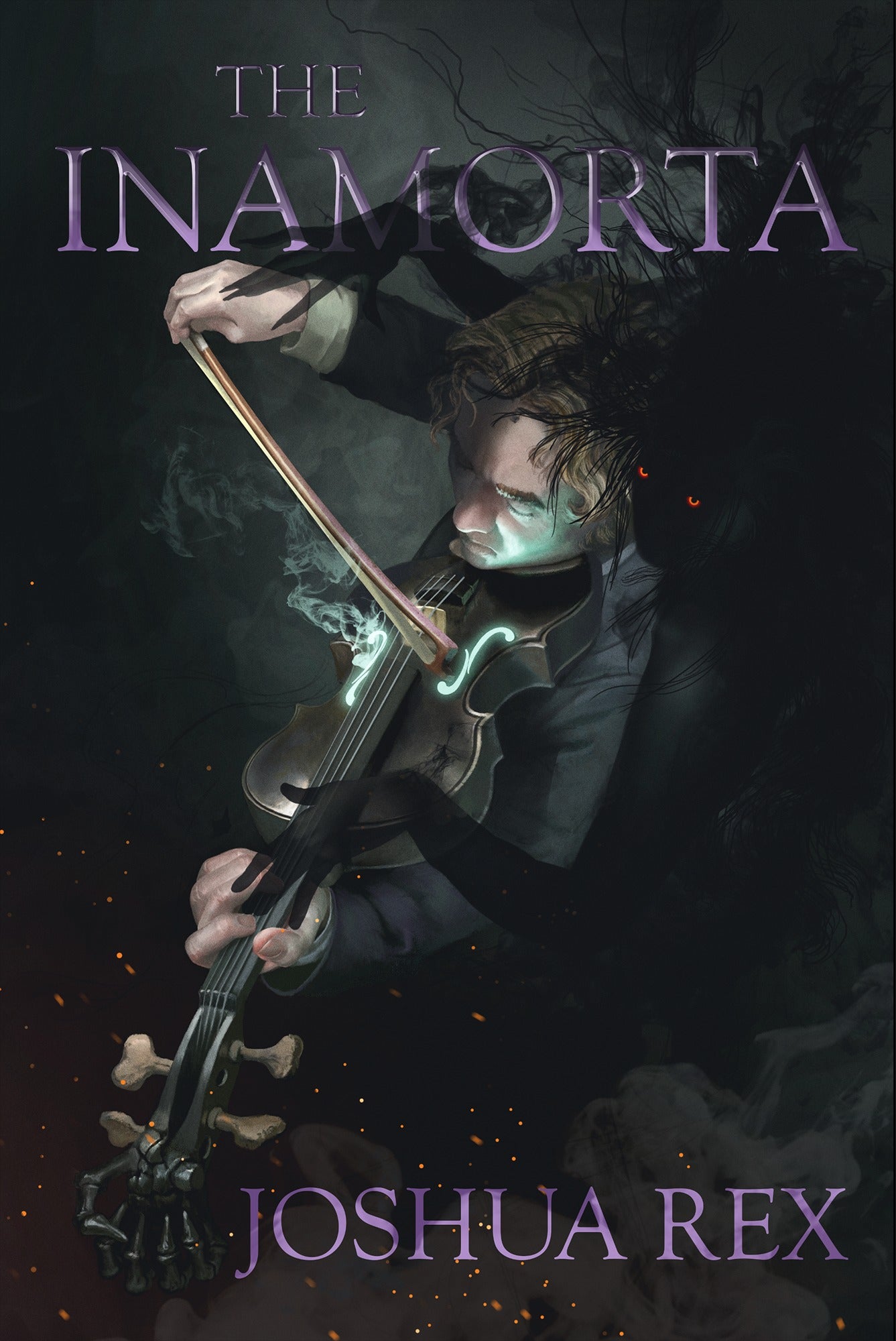

November, 1799. Jonas Layne, the acclaimed “world’s greatest violist” who performs on a notorious viola known as the Inamorta whose previous owners all have succumbed to violent fates, begins keeping a journal. He is weary of the touring life and plagued by a terrifying reoccurring nightmare of a monstrous wolf. When Jonas and his father/piano accompanist Theodore are commissioned by the enigmatic Count Rufus Canis, they travel to his residence, Teethesgate Castle, in the hinterland. Teethsgate is eccentrically opulent and grandiose, but things there are not as they seem. Something ghostly clings to the castle and its bizarre family. In Larmes Harbor, the decrepit village south of the castle, people are disappearing, and the Count’s seductive daughter, Daeva, has a fearful and powerful secret which will force Jonas to confront one of his own—and the reality that his nightmare might be more premonition than dream.

A New Ghost House Book!

EDITIONS

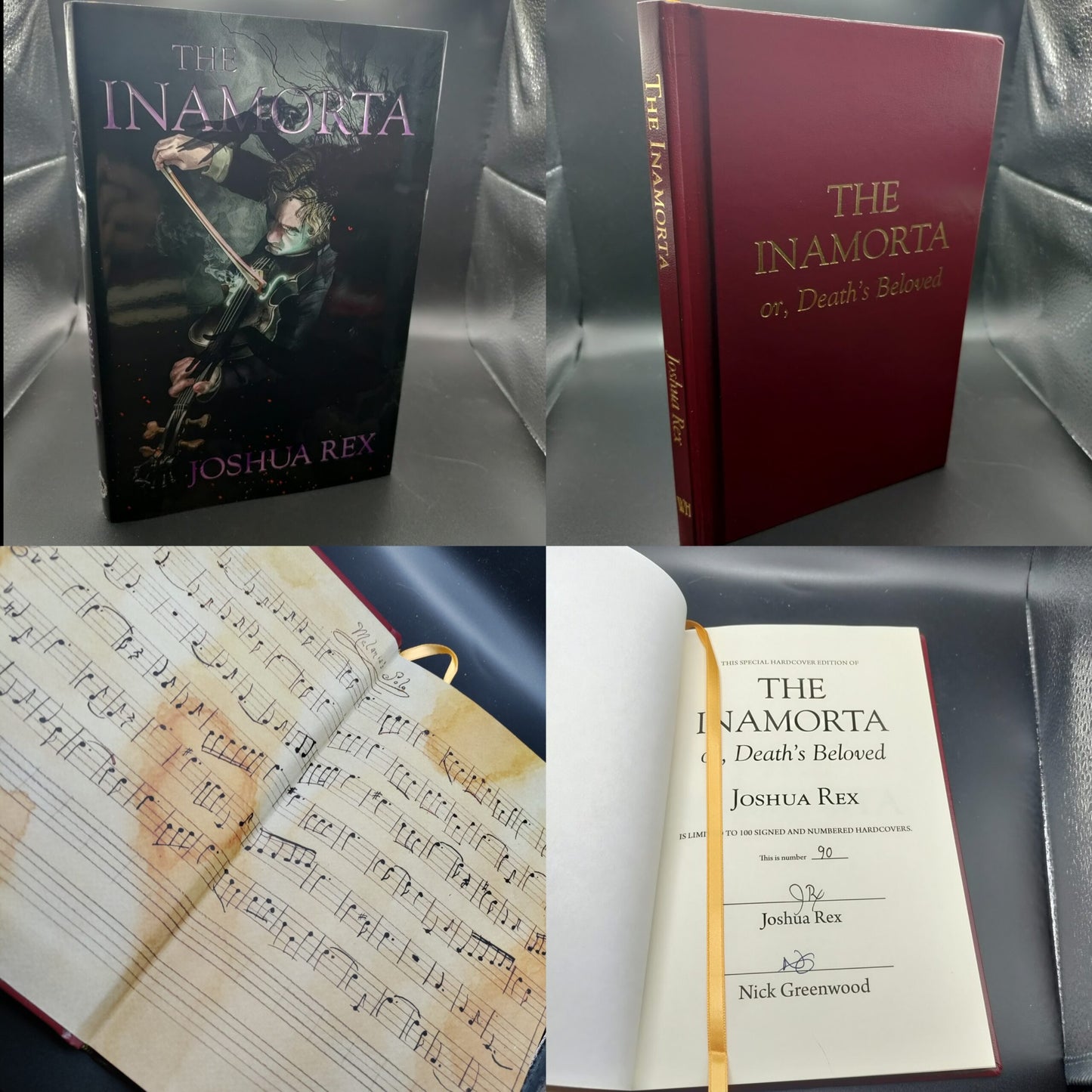

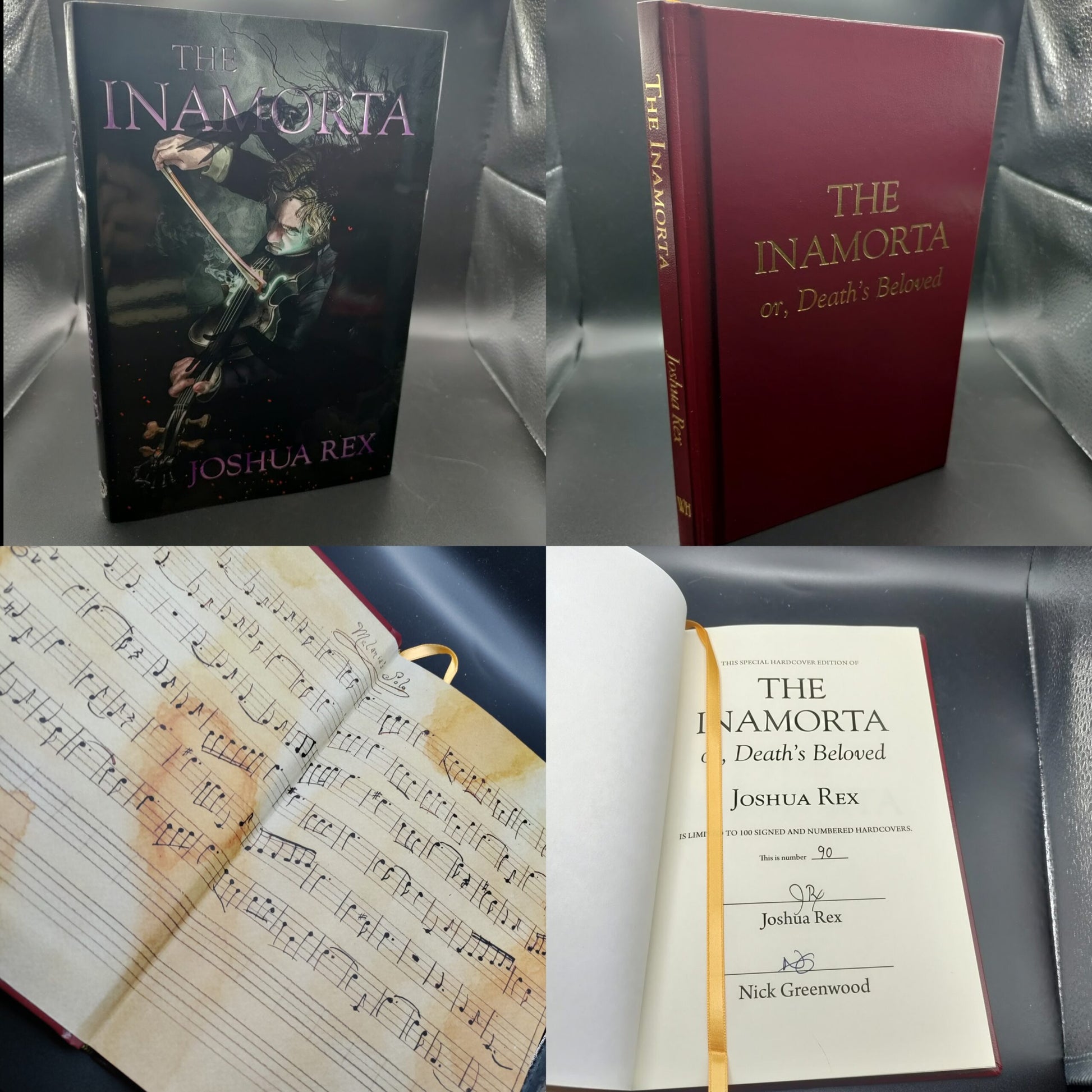

Signed & Numbered Limited Edition Hardcover

- Signed by Author Joshua Rex and Artist Nick Greenwood

- Hand-Numbered 1 to 100

- Color Dust Jacket

- Spine Stamping

- Color Endsheets

- Page Count: 220

- In Stock

Signed & Numbered Trade Paperback

- Signed by Author Tony Richards

- Hand-Numbered 1 to 100

- Color Cover

- Page Count: 220

- In Stock

A Warning to the Reader:

The text you are about to read has been transcribed (and typeset and published by Weird House Press) from a journal which I discovered at the bottom of a tattered viola case at an antique dealer’s in the town of Rye, E—. I was spending the weekend there several years ago during a research trip, wandering its meandering brick streets and admiring the scores of Tudor period houses with their sharply-gabled roofs and small windows with wavy leaded panes. The weather had been quite brutal—hard rain and rogue winds which prevented me from exploring in as much detail that I had intended the many architectural wonders of the little hamlet on the sea.

Upon one such stormy early afternoon, I had sought refuge in the antique dealer’s. This shop was located on the first level of a leaning, half-timbered structure which I guessed to be at least five hundred years old. Within was the usual junk mixed with rarities: ephemera, quotidian objects, objects of value which were absurdly overpriced. In one windowless and silent corner, while perusing a series of phantom-like Victorian glass plate negatives, I spotted an instrument case lying on the bottom plank of a crude wooden shelf. As I once worked as a luthier many years ago, I am always intrigued by such objects, hoping with a treasure seeker’s enthusiasm that I might uncover some masterpiece of the Italian school forgotten and neglected amidst the desultory bric-a-brac of centuries.

Casting the plates aside, I crouched, placed the case on my lap and opened it. To my dismay, no instrument lay within. A suffocating must emanating from the padded interior caused me to turn my head for a moment, and when I at last looked back I noticed the small book lying within. It was maroon, with gold embossed lettering, and two words on the cover in block capitals: THE INAMORTA. The unlined, cream-laid pages within were filled with a fine script written in pale brown ink which grew increasingly erratic, even frantic, the further it progressed. It was an incredible, terrifying story—almost certainly a work of fiction. I hesitate to confirm that it is indeed such due to the eerie urgency in the hand which penned it, as well as the locations and the protagonist and his father that it mentions, which I have through subsequent research confirmed to have all actually existed.

The proprietor of this shop, a gaunt and willowy gentleman of advanced years who informed me that his family had lived in the town since before the Norman Conquest, was attentive to my inquiries regarding the instrument-less case, and the surprisingly well-preserved piece of writing within. When I asked why the journal—an historic piece penned by a most illustrious classical musician—had not been separated from the case, the proprietor said that he had felt a powerful intuition that to do so would “bring ruin” upon him and his shop, and that what he really wanted was to “be rid of the thing altogether”. Shrewdly I offered him an absurdly low price, which to my surprise he accepted eagerly with a grin, baring hideously decayed and crooked teeth. Greatly satisfied with my new acquisition, I left the shop, removed the book and tossed the rotten case in a trash bin behind a fruit seller’s. Then I returned to my quaint room at the Mermaid Inn to read the little tome in full. Later that night, I was woken by the low humming of some dark and minor key musical passage. I could not determine if it was coming from within my room, outside my window, or inside my own head. I have heard this song again and again over the years, accompanied sometimes by shifting shadows in my room where I lay still in dread upon my bed during the long hours between night and morning.

Has some trace of the horror told in this story permeated these pages? If so, is it communicable? I cannot determine that song I hear—the one which surfaces in my mind like something emerging from black water under a full moon, something with red eyes and char-black hair—is an existing piece of music. Nor is the dark melody a product of my own decidedly uncreative and scholarly-driven mind. What I am certain of is that both the story and its song have become and increasing distraction for me—an obsession that has led me towards an ever increasing madness. Therefore, a word of warning to all you who peruse these pages: what follows is a sort of consuming narrative spell, and a music which animates the shadows.

– JRX

The Story of the Endpapers for THE INAMORTA

by Joshua Rex

I’ve always wished I were a trained musician. Some kids are forced to take years of piano lessons—I wanted to be one of those kids, but alas it wasn’t in the family budget. I wrote songs in my teens, took violin lessons and taught myself piano fundamentals in my twenties. Somewhere along the line I fell in love with the viola, and obsessively sought out music written for it. The solo works in particular are some of the most emotive and powerful written for any viol family instrument (see Vieuxtemps “Capriccio,” and Britten’s “Elegy”). In the latter, the wordless yearning is so similar to a human’s mourning wail that it is easy to forget it’s coming from a box of wood and strings.

I was greatly influenced by this notion while writing The Inamorta. In it, Jonas Layne’s eponymous instrument sounds so close to the human voice that it’s uncanny (the reason for this, of course, later becomes apparent). While working on the novella, I often wondered what the viola would sound like; as a result, a song began to develop in my mind. The nascent theme grew in complexity and length as I revised the book, and after a while the piece became so integral to the story I knew I had to include it.

But how? I thought if I transposed the piece to guitar or piano I could ask a violist to perform it, but I couldn’t find one. Fortunately, however, I had made friends with S. T. Joshi—the preeminent scholar, author, and also accomplished musician. S.T. did editorial work on The Inamorta and was well acquainted with the story. So I pitched him a crazy idea: If I recorded myself humming the piece, could he transpose it music? To my surprise, he was willing to give it a try, and less than a week later I received not only sheet music for the piece but a viola simulation performance of it (which was 95% close to the music in my head). Hearing what had to that point been only in my head was an astounding moment.

The sheet music enabled me to create a faux musical “score” for the composition (entitled “Melania’s Lament”). I had spent a good deal of my late twenties and early thirties as an artist, and produced a series of reproduced historical documents called Primary Sources. Most of these were sheets of paper with letters or musical notes drawn in brown pen and ink, and then stained with tea; I utilized the same process to create the score.

The endpapers for The Inamorta are, for me, sort of a miracle. They are the fulfillment of a long desire to compose music for an instrument I love but cannot play. They give aural agency to the frightful instrument in the story. They are a testament to true collaboration (without S.T.’s help they wouldn’t exist). Finally, they are the intersection point of the work I’ve done as a songwriter, artist, and author.

CONTRIBUTORS

Author: Joshua Rex

Front Cover Art: Nick Greenwood

Editor: Joe Morey

PRAISE FOR JOSHUA REX

“I love to read Josh Rex. He’s the poet’s novelist. Dark, funny, mysterious–Josh creates pages that are a joy to get lost in. I would lavish more praise on him if I weren’t so jealous of his writing.”

— NY Times Best-Selling Novelist Thomas Lennon

“From the stark warning for our times in the first story to the poetic beauty of the last paragraph, this is a collection that won’t fail to impress, intrigue and enthrall. Joshua Rex is a fantastic new talent with a deep appreciation of history, an eye for the telling metaphor and above all a flair for storytelling.”

— Allison Littlewood

“Joshua Rex’s stylistic execution is both distinct and discrete, deftly-crafting tales that coax his audience into a sort of uncanny collusion. The stories collected in The Descent and Other Strange Stories entangle the reader like a winding sheet.”

— Clint Smith, author of The Skeleton Melodies

“Joshua Rex continues to demonstrate why he is one of the most dynamic young writers in the weird fiction field. The Inamorta is a splendid example of old-time Gothicism–a Golgotha of horror and grue livened with deft character portrayal and crisp narrative pacing. And in its attempt to achieve the supremely difficult task of evoking terror from music, it is a thunderous success.”

— S. T. Joshi

Share